There are a whole lot of reasons why I love Majora’s Mask more than Ocarina of Time. I usually start by talking about Clock Town and the three-day cycle. I might mention the relative pre-eminence of the overworld, the transformation masks, and the general aura of dread. I might go on for a bit about how dour and Campbell-by-numbers I find Ocarina’s first act, and how those earth tones make me long for Super Mario 64.

But the simplest reason to explain is that Majora’s Mask has a better villain.

The Zelda games that feature Ganon or Ganondorf as their ultimate villain are often great, but they’re great in spite of their villain. Their villain clearly doesn’t matter all that much. Games like The Legend of Zelda and Ocarina of Time are working in the same tradition as The Lord of the Rings or Doctor Who’s Dalek stories: the enemy is simple, evil, and not burdened with unnecessary depth of character. The story focusses not on the central conflict itself, but on the struggles the characters go through to eliminate an opponent that is remote, sometimes to the point of being largely absent from the story.

I love a Totemic Evil as much as anybody. But Ganondorf is, by design, a less rich character than many less structurally important characters in Ocarina. The Skull Kid, on the other hand, is the diseased heart of Majora’s Mask. He is a lonely child given sudden power, who takes the opportunity to exact revenge on the world he felt denied him his entitlement. You can recognize him from real life, or at least the internet.

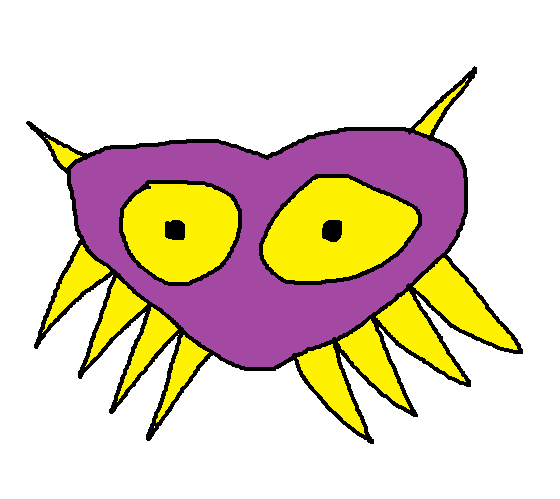

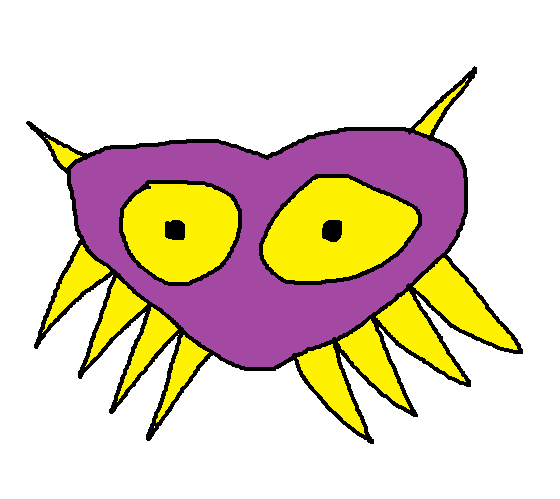

The Skull Kid and his mask are triumphs of design; his gait is a triumph of animation; the scene where he transforms Link into a Deku scrub whilst hovering in a pair of spotlights is a triumph of staging. He is instantly memorable, and even though he is also relatively absent from long stretches of the story, he remains a highlight.

Every time I’ve seen the ending of the game, I feel conflicted about whether he deserves forgiveness. The wise old giants seem to think so, and there’s an argument to be made that he isn’t truly responsible for his actions. But living in a world where young men routinely perpetrate unthinkable violence out of a sense of alienation gives me pause.