Shakespeare wrote more lines of dialogue for Henry V than any other character in his corpus. True, Hamlet speaks more lines within a single play. But Henry V is the protagonist of not just one but three plays: the one that bears his name, and also both parts of Henry IV, in which he appears as Prince Hal. Across those three plays we see him as a wayward youth, rejecting his father’s attempts to set him right. We see him gradually recognizing that the responsibility of kingship is coming his way whether he wants it or not. We watch him repudiate Falstaff, his mentor in the ways of drink and mischief. And we see him transform into a strong king and military leader.

As we explore Clock Town in Majora’s Mask, we discover that Termina also has a Prince Hal: the mayor’s son, Kafei. Much of our time in Clock Town is dedicated to filling in the details of Kafei’s life story and character. You’ll probably find your way to city hall fairly early in your time with the game. If you do, you’ll meet the Henry IV of Clock Town: not Kafei’s father, Mayor Dotour, no no. His mother, Madame Aroma: a vivacious and overbearing society woman who fully eclipses her mousy husband. She is the formidable presence against which Kafei seems to have rebelled. But we don’t know that yet. All we know is that he’s gone missing, mere days before he was set to be married. The impropriety! The shame.

We discover Kafei’s deeds and misdeeds through interviews with Clock Town’s other various interested parties. His fiance, Anju (whose name sounds like “Anjou,” i.e. Margaret of Anjou, another historical figure who appears in Shakespeare’s history plays, but not in a way that seems relevant here), is fully confident that Kafei loves her and will return to her, pending disaster. For a while, that may seem hard to believe. We learn Kafei’s backstory from his closest childhood friend, the prematurely balding proprietor of the Curiosity Shop, which buys and sells stolen goods. This is Kafei’s misleader, his Falstaff, albeit without the bulk or the wit. Somehow, Kafei continues to trust this man. Perhaps that alone is enough to sow doubt in a prejudiced mind.

Anju, incidentally, is the daughter of a prominent business family. Her mother runs the Stock Pot Inn, apparently the only hotel in Clock Town. Perhaps her marriage to Kafei would be politically expedient for the Dotour family. Perhaps Kafei has frittered away the family fortune, and a marriage into money would help him pay his debts. Even Anju’s mother has her private suspicions: in one of the most effective and well-hidden scenes in the game, you can eavesdrop on a conversation where Anju’s mother tries to convince her daughter that Kafei is a roustabout who’s run off with Cremia the milkmaid.

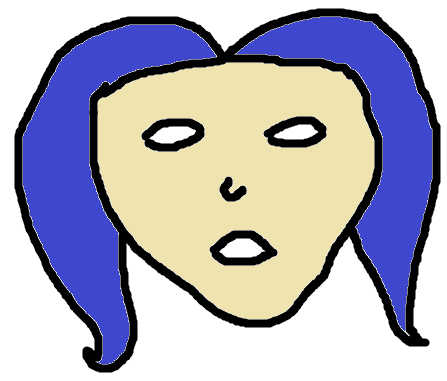

Lending credence to all of these suspicions is the fact that we see Kafei repeatedly. We know what he looks like, and that his defining feature is a striking head of bright blue hair. At the beginning of every three-day cycle we see a person, seemingly a child, emerging from the archway to the laundry pool to drop a letter in the mailbox. This child is not the age we know Kafei to be, and he’s hiding his face behind a mask. He won’t talk to us, and hurries immediately back into a door that we later discover leads into the back room of the Curiosity Shop. But it’s clearly him, and his behaviour and circumstances add to the mystery.

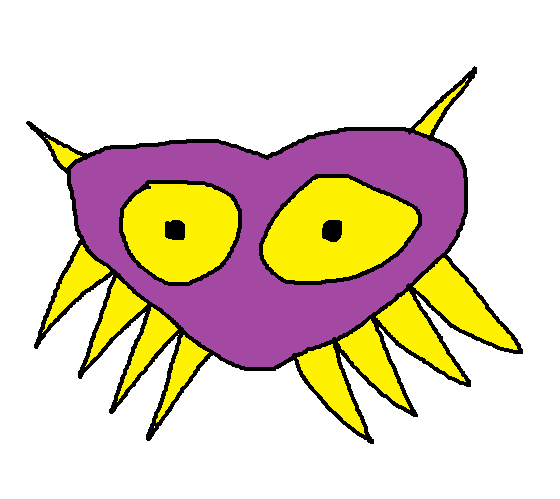

The poignant twist at the end of all this is that Kafei has reformed, and that his love for Anju is genuine. Maybe she’s the reason he’s put his old ways behind him. He hasn’t run off with Cremia: he’s been transformed into a child by the game’s main antagonist, the Skull Kid, who otherwise has nothing to do with any of this. What specific grudge the Skull Kid ever had against Kafei and Anju is left to the player’s imagination.

So is the reason why “transformed into a child” was the Skull Kid’s curse of choice–and why Kafei is so upset about this that he feels he has to keep it secret from his fiancé. But it does lend an unexpected perversity to Kafei and Anju’s eventual reunion. If you manage to complete the onerous and deadline-heavy sidequest that allows for this event, you witness Kafei and Anju together once more in a room at the Stock Pot Inn. Tatl remarks that they look more like a mother and child than like lovers. Kafei stands waist-high to Anju, looking like the thing he fears he still is: a child, moving through the world without fear of responsibility or consequence. He stands before the inspiration for his sudden maturity, embarrassed to have so recently been Prince Hal, and to be only midway through his transformation into Henry V.

What happens next kills any doubt that Kafei is a new man: he stays with Anju in Clock Town while the moon falls. He had every opportunity to flee, and instead he spent his time vainly trying to lift his curse so he could stand before Anju as the person she believes him to be. Realising that she also could have fled but chose to keep faith, he goes to her. They could have fled together if Kafei had only overcome his vanity and self-consciousness. But again, his maturity is still in progress, and the next best thing to living together is dying together. The story’s setup is pulled straight from Shakespeare, but its conclusion is a melancholy fable fit for a Decemberists song. Depending how well you play the game, Kafei and Anju could die alone dozens of times before you manage to reunite them. Exactly one time, they die together.

Exactly one time after that, they survive to be married. But even the wedding scene is a compromised affair: Kafei is nowhere to be seen, presumably because the time-pressed development team had to throw together the end credits too quickly to justify making a character model for his adult self. So, we witness the ceremony partially from his perspective. That’s not entirely new: since we first met Madame Aroma, Link’s been occasionally wearing a mask of Kafei to indicate that we’re involved in the search for him. Here we are at the wedding, looking through his eyes once more. This time, they’re the eyes of a grown man. But behind those eyes, there may still be a child, striving to live up to his promise:

“So, when this loose behavior I throw off

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men's hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glittering o'er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I'll so offend, to make offence a skill;

Redeeming time when men think least I will.”