There is Normal Zelda and there is Weird Zelda.

The first six games in the Zelda series are a secret trilogy of pairs, each containing a Normal Zelda and its Weird Zelda doppelganger. It’s not unusual for an artist or group of artists to follow up an unqualified success with something bizarre, overambitious and completely different (see also: the White Album, Breakfast of Champions, Howl’s Moving Castle). But for a single body of work to traipse back and forth between these two poles so reliably is almost unheard of. For its first fourteen years, Zelda had two modes: unaccountable self-assurance and wanton experimentation. There are no tentative steps or half measures. There’s no Rubber Soul, no Mother Night and no Kiki’s Delivery Service anywhere in sight–let alone a Beatles for Sale. The first six Zeldas are a parade of Sgt. Peppers and White Albums marching two by two. To understand how Majora’s Mask fits into this lineage, let’s take inventory of its predecessors.

For our purposes, The Legend of Zelda is an urtext: a basis upon which to write variations and commit subversions. But even this urtext is in dialogue with an older sibling. The Legend of Zelda’s opening screen famously subverts the opening screen of Super Mario Bros.’ World 1-1, where Mario’s fundamental rule of “go right” is overwritten with “go anywhere.” This innovation paid off.

Odd then, that the overworld of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link should immediately present the player with a brown dirt path of least resistance that leads you exactly where you need to go. (Granted, the path branches once before you get there, and you’ve got no obligation to stay on it either way. But you depart from the path at the peril of unwelcome combat encounters, and a single branching choice is hardly generous compared with the openness of TLoZ’s early game.) Add this to the pile of new elements introduced here, along with the side scrolling dungeons and combat encounters and the grindy RPG system.

All of these elements conspire to give Zelda II a black sheep reputation–even a bad reputation. And while the game is deeply unfriendly and often tedious, there are many new elements here that will go on to define Zelda in the future. For our purposes, the most relevant of these is the presence of towns. In the first game, Link is presented as a man lost in the wilderness. His only contacts are an old man who gives him a sword, a merchant, an old woman who makes him potions, and an anomalous benign Moblin that gives him money–each of whom is as solitary and alienated as Link himself. The Legend of Zelda presents the world as a vast wilderness populated exclusively with monsters and eccentric hermits. The Adventure of Link presents something representing civilization for the first time. For all its problems, Zelda II’s repeating structure of town-wilderness-dungeon sets the template for nearly all of the subsequent games.

I played both of the Zelda titles for the NES at a point in my life when I wasn’t playing other games, and had the time and patience (and save states) to get through them. For science. Or history, or something. If you’re interested in these games but haven’t played them yet, let me offer a bit of public service journalism: from a contemporary perspective, both of the NES Zeldas are equally deserving of exactly one hour of your time. The first game is rightly held up as a watershed moment in videogame history, but its exclusive focus on exploration and combat with only the barest hint of narrative makes it a rough sit for a modern player. The second game is infuriating in many ways, but it’s also stranger and richer in detail. Neither game is actively enjoyable; both are fascinating as artefacts. With both games rendered museum pieces by the passage of time, they’re equal now.

In its final moments, Zelda II presents Link with a doppelganger that he must kill. If Zelda II is a doppelganger in itself, we might look at this final fight and see the developers observing their bizarre sequel and saying “destroy it–we’ll never do this again.” But they did do it again. Zelda II is the wellspring of Weird Zelda: it is a resolutely non-laurel-resting creation that fails abjectly as a follow-up to its hit predecessor because it is something else entirely. It feels terrible to play, but it also has a guy who tells you “I am Error” as if it’s totally normal, and you will never forget that.

Zelda II is a White Album composed of ten percent “Blackbird” and ninety percent “Revolution 9.” That balance will have to shift if it’s ever going to work, but the pattern has already begun.

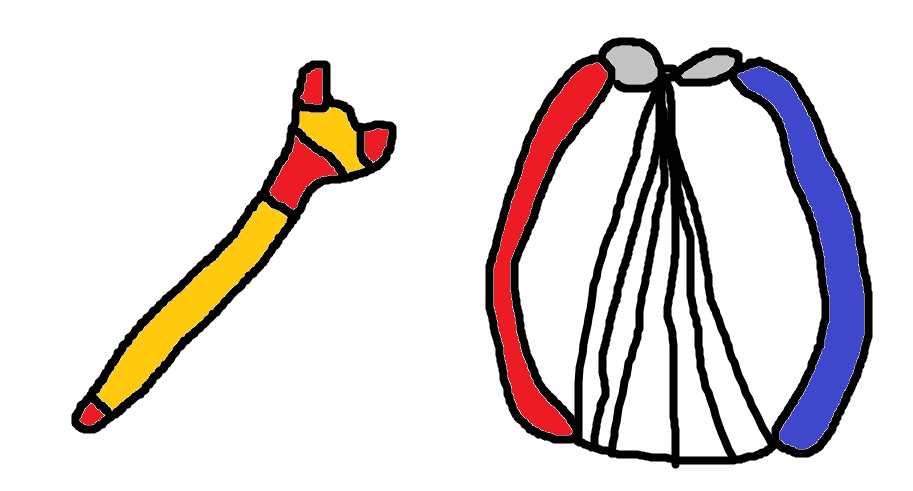

The final fight of Zelda II set this series’ obsession with dark doubles in motion, and A Link to the Past ran with it. The first Zelda might well have had a dark double in its sequel, but A Link to the Past one-ups it easily by presenting a shadow self within its own boundaries. It is the first game in the series that presents the player with two related maps to traverse: the Light World and the Dark World.

Nevertheless, the rules have been established. A successful Zelda game must be followed by a shadow sequel, no matter how much doubling exists in the game itself. This time, instead of tacking on new mechanics and transgressing genre boundaries, the sequel transgresses the boundary between wakefulness and sleep. Link’s Awakening is the most surreal experience in the series so far. It famously presents characters and iconography from the Mario universe, suggesting that intellectual properties can dream of each other.

Link’s Awakening also transgresses a hardware boundary, bringing the Zelda series to a handheld for the first time. The limitations of the Game Boy amplify the game’s dreamlike nature: Link’s Awakening looks like a shallow facsimile of A Link to the Past’s waking world, even as it reveals its own depths. (The recent remake of Link’s Awakening for the Switch damages this impression by amplifying the original’s cartoonishness. With a more intentional aesthetic, the game no longer possesses the uncanniness of the Game Boy’s deficient but evocative imitation of a console–which is roughly analogous to the dream world’s deficient but evocative imitation of real life.)

Link’s Awakening strengthened the Weird Zelda template. It is a small, self-contained object that declines to double itself in the manner of its predecessor, knowing that it is, in itself, an uncanny double. It takes place in a dreamlike mirror world where familiar people aren’t quite themselves. And, unlike the previous Weird Zelda title, it is definitely good.

It’s hard to decide what may have been the greater challenge: making the first 3D Zelda game, or rushing out its sequel in one year. Perhaps it was useful for the developers of Majora’s Mask to have the example of Link’s Awakening before them. Elements of that game anticipate their best and most counterintuitive idea: to reuse character models from Ocarina of Time, but not have them represent the same characters. Reusing the character models was a natural time-saving imperative. But having made that decision, it would have been more obvious to set the sequel to Ocarina in the same world, with some of the same characters. Instead, the familiar faces we meet appear with entirely different identities.

Doppelgangers have been appearing in this series since the final fight of Zelda II. It seems natural that Zelda II’s most gifted child–the apex of Weird Zelda–should consist of them almost entirely. Indeed, virtually everything about Majora’s Mask traces back to the two prior Weird Zeldas. Like Zelda II, it revels in uncanny and inexplicable NPC dialogue, and it layers risky new systems on top of a perfectly successful formula. It emphasises the presence of civilization in the world, rather than simply wilderness. And like Link’s Awakening, it tears Link away from Hyrule and plops him down in a different, more dreamlike place. Ocarina took after A Link to the Past in the sense that it contains two worlds within itself. And Majora takes after Link’s Awakening in presenting a single, stable location that is nevertheless a subconscious reflection of its predecessor.

The Weird Zeldas are each inextricably partnered with their respective Normal Zeldas, but they also form a trilogy in themselves: an estranged family; a witches’ coven. They are each darker in subject than their predecessors, but lighter in tone. They take the customary hero’s journey narrative outside the realm of high fantasy and into the realm of dreams and the darkness of the subconscious. Majora’s Mask is the culmination of this tendency: the sum of Weird Zeldas past, and the ultimate negation of each of their counterparts.

Ocarina and Majora marked the end of Nintendo’s procession of Sgt. Peppers and White Albums. But the sense that Zeldas come in pairs survived for one more round. One year after Majora’s Mask, Nintendo published Oracle of Seasons and Oracle of Ages–but did not develop them, having temporarily farmed out the handheld Zeldas to Capcom–on the same day. They’re intentionally paired, each a sequel to the other depending on the order in which you play them. (Evidently there was meant to be a third game, reflecting the series’ core image of the Triforce, but it was cancelled, revealing that even fate recognizes the number two as the core of Zelda.)

Both games find Capcom visibly obsessing over the legacy of the intellectual property they’ve just been handed the keys to. Perhaps inevitably, each game in this explicit pair also finds itself partnered with another game from the series’ past. Oracle of Seasons’ large, contiguous overworld map pairs it implicitly with the original Legend of Zelda, as do its references to that game’s mysterious old hermit living under a tree. Ages instead contains two mirrored world maps, a reflection of A Link to the Past. Intentionally or not, Capcom created two new shadow sequels to the tentpoles of 2D Zelda.

Together, the duology finds itself in yet another shadow pairing, with their predecessor in the series’ procession of pairs. These are the first 2D Zelda games developed in the era of 3D Zelda, and they exist in dialogue with the N64 Zeldas almost by default. Both games feature characters and iconography that we previously thought only existed in either Hyrule or Termina, but somehow have found themselves in two games that take place in neither. For the first time, we see Gorons in two dimensions. The Oracle games seem to be seeking a purpose for 2D Zelda in this new age, asking what can be done better in this format. (One answer is water-based dungeons. The version of Jabu-Jabu in Oracle of Ages finds Link adjusting the water level across dungeon floors in a similar manner to Ocarina’s Water Temple–which is much more satisfying when “flooded” vs. “non-flooded” is a binary state, as 2D dungeon design requires.)

Neither game fits neatly into our Normal basket, nor our Weird one. Both games take place outside Hyrule, unlike the Normal Zeldas. But they lack the dreamlike anxiety of the Weird Zeldas, and their mutual nostalgia seems fixed largely on the tentpoles of the series’ past–not the subversions. However, alongside a few icons from Ocarina of Time, some characters and images from Majora’s Mask creep in: Tingle, the postman, the toilet hand. The Oracle games break the cycle of Normal and Weird Zeldas by pledging allegiance to the Normal for two games in a row. But the Weird is scribbling in the margins, and it may continue to do so.

There may be obvious pairings of Normal and Weird Zeldas in the series beyond this point. I don’t have the familiarity to say. However, as I’m writing this, the most recent mainline Zelda is a mirror-twin of the most acclaimed game in the franchise thus far, which was itself a refocus on what made the original Legend of Zelda so revolutionary. The legacy of Majora’s Mask–or maybe it's more accurate to say the legacy of Zelda II–lives on.